Spousal maintenance and the clean break principle!

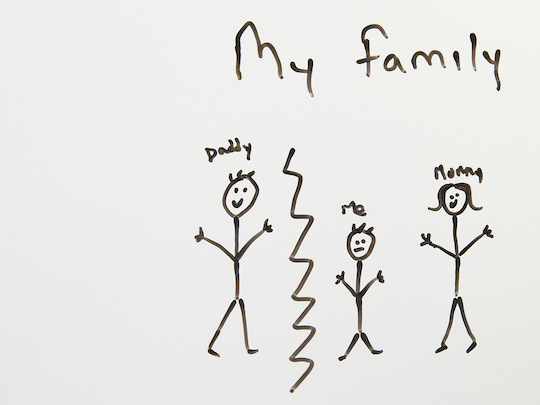

Where a relationship has broken down and the parties have separated, it is in the interest of both parties to end the financial relationship between them once and for all. This financial separation will allow each party to move on in their lives without being financially tied to the other party. Naturally this is not always possible, but where it can occur it should.

Section 81 of the Family Law Act 1975 for married couples and section 90ST for de facto couples seeks to end the financial relations between parties once and for all. Section 81 says:

In proceedings under this Part, other than proceedings under section 78 or proceedings with respect to maintenance payable during the subsistence of a marriage, the court shall, as far as practicable, make such orders as will finally determine the financial relationships between the parties to the marriage and avoid further proceedings between them.

The ideal solution between separating couples is to finalise the financial separation amicably without the need of the court. This can be achieved through the assistance of lawyers by implementing a binding financial agreement between the parties. When this cannot occur, the court will need to be engaged to enable a clean break between the parties if it is appropriate under the circumstance.

Where a spousal maintenance order is issued by the court, it will not stop the court at a later date making further maintenance orders. Under section 80(2) of the Act it provides that an “order that a specified transfer or settlement or property be made by way of maintenance for a party to a marriage, or of any other order under Pt VIII, in relation to the maintenance of a party to a marriage does not prevent the court from making a subsequent order in relation to the maintenance of the party.” Section 90SS(2) which applies to de facto couples is similar to section 80(2).

There are situations where the clean break principle for spousal maintenance under sections 81 for married couples and 90ST for de facto couples of the Act are not appropriate; which some of these circumstances include:

(a) Where periodic spousal maintenance is necessary due to a lack of property to divide to meet the maintenance needs of the parties.

(b) As each parties circumstance changes, periodic spousal maintenance is preferable, which will allow for adjustment in maintenance provisions to occur amicably or through the court. Under section 83 or section 90SI of the Act, periodic maintenance orders are variable when circumstances change.

(c) Under sections 79(4)(d) and 90SF(4)(d) of the Act specifically direct the court to take into account the effect of any proposed order upon the earning capacity of either party. Making a periodic maintenance order rather then a lump sum maintenance order may enable the payer to keep the capital assets of a business intact if that is the case.

(d) The question of spousal maintenance may be left open if it is unclear how much is required by a party in the future.

(e) There is no power to terminate the court’s maintenance jurisdiction by court order, which means spousal maintenance can be adjusted at anytime by the court on reasonable grounds.

In Anast and Anastopoulos (1982) the trial judge ordered a lump sum spousal maintenance amount of $35,000 to the wife. The wife appealed the decision. The Full Court held that as the wife had limited working experience, aged 50 years old, and had the care of the two children, with her financial future uncertain, the $35,000 would be treated as property, meaning part of the division of the assets and not as spousal maintenance. The court further held that the wife could still apply for spousal maintenance either as a lump sum or as a periodic payment at a later date as required.

In Bignold and Bignold (1979) the marriage ended after 37 years. The court awarded the wife $110,000 out of a $265,000 asset pool. The court was asked to consider the payment of $110,000 over a period of 18 months. The court rejected this approach as the end result would be the same and the court wanted to bring a conclusion to the financial relationship between the parties.

In AM and KAO [2006] the court held there is no requirement that spousal maintenance have a periodic predetermined end date. What this means is that if a final settlement date for maintenance is sought by a party to a relationship, the court may be reluctant to put an end date on any order for spousal maintenance.

In Bucknell & Bucknell [2009] the court said:

A court making a spousal maintenance order often has a choice between, on the one hand, leaving the order to operate for an indefinite period, knowing that section 83 of the Act provides for variation if circumstances so change that variation is justified or, on the other hand, fixing a date of cessation, which often involves a prediction, albeit on the balance of probabilities.

The clean break principle for spousal maintenance is a difficult fact to balance when there is insufficient property to be divided between the parties to end the financial relationship. Sometimes it will be necessary to have an ongoing financial relationship due to the need of one of the parties over an extended period of time. The appropriate solution for separating couples is to resolve all financial matters amicably, and the first step is to get that legal advice to protect your legal rights and interests.

The comments in the aforementioned do not constitute legal advice and are general in nature, and if legal advice is required please contact: John Melis at Legal AU Pty Ltd (03) 9999 7799 www.legalau.com

Legal AU Pty Ltd Lawyers are “Liability limited by a Scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation.”